Can compostable bioplastics play a valuable role in the circular economy? Why is it a market to be developed beyond shopping bags? Has the EU done enough to support the market? Has Italy?

Answering these and other questions is Stefan Barot, since July 2020 Managing Director and CEO of Biotec-Biologische Naturverpackungen, part of the French group SPHERE, which has developed and produced packaging and bags for food contact and household waste since 1976.

In 2021 the plastics tax in Italy should go into effect: what is your position on the prospect of taxing bioplastics? What do you think of the idea of levying the tax along the supply chain and not at the source, i.e., the manufacturers of polymers and compounds?

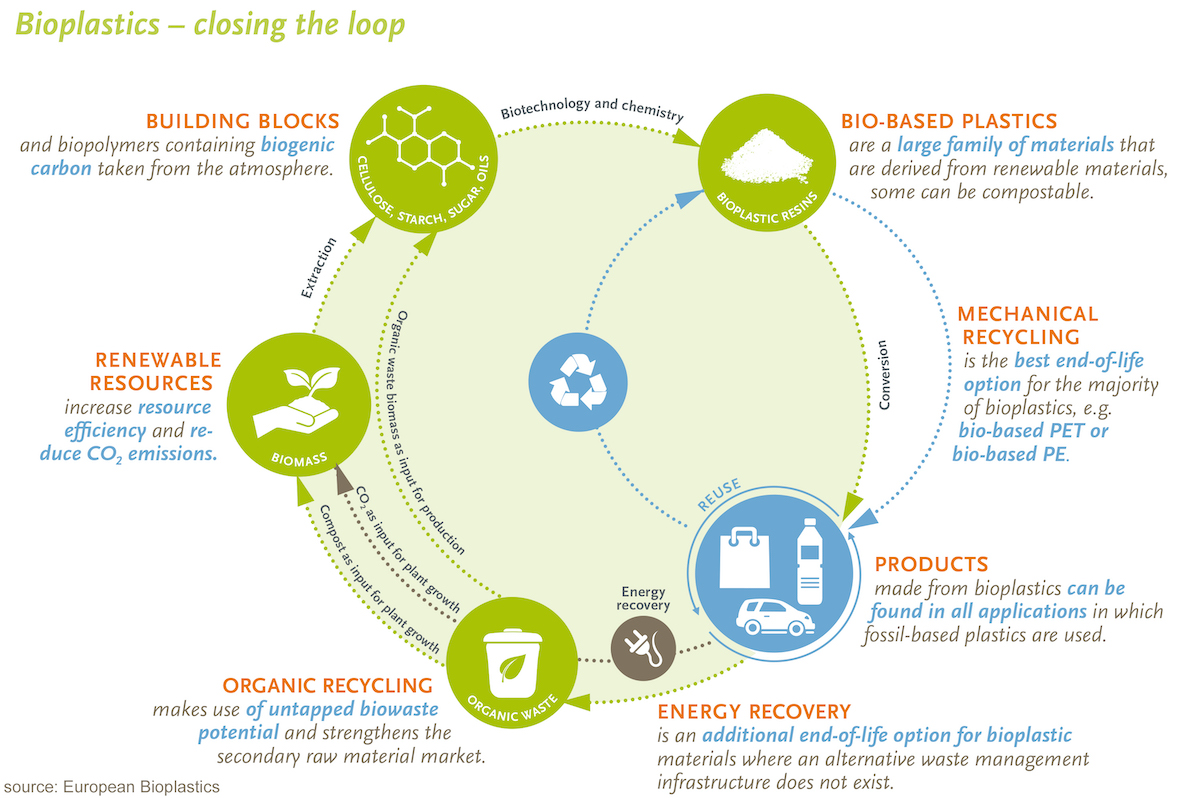

As a concept I think that it is wrong to levy a tax on polymers without using this money to build the infrastructure to recycle and reuse these same polymers. Currently only a fraction of the polymers are recycled and there is quite a lot of contamination in the recycled polymer stream. The fact that only 2-2.5% are actually recycled into the same item and the rest is downgraded shows the challenge we have ahead, so taxing without building the facilities does not serve the purpose to achieve more circularity. Levying these taxes along the value chain also doesn’t make sense. It is probably better levying at the source.

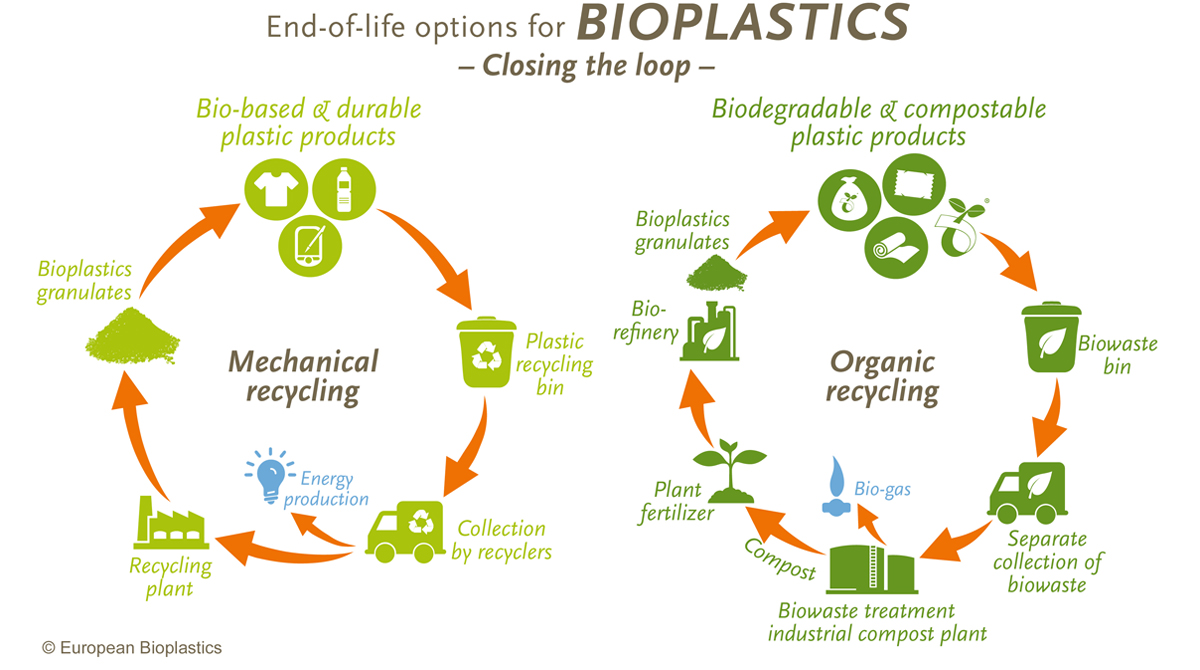

To compost biomass is organic recycling, and biopolymers help to divert biomass from landfill and incineration, which support this organic recycling. Where this composting infrastructure already exists, bioplastics should be exempted as well because recycled polymers are exempted from this tax later on. Consequently biopolymers that help to recycle biomass should be exempted too.

The European SUP directive does not include exemptions for single-use items produced with bioplastics obtained through chemical industrial processes. Don’t you find this to be a contradiction, given that 20 years ago the EU accepted the standard EN 13432 on the use of compostable bioplastics for shopping bags?

Indeed, there appears to be a contradiction. What we do now with the SUP is to forbid certain articles, which is a wake-up call, but will make the situation worse for certain articles. When banning an article, we always need to consider the alternative. Let’s look at plastic cups and the replacement with ceramics: a ceramic cup needs much more energy to be produced; we will need to wash and reuse a ceramic at least 200 times before it has a better CO2 balance than a plastic cup. And while the plastic cup can be composted or recycled, all you can do with ceramics is to smash them up and use them in road construction, in many cases resulting in a worse outcome for the environment. Taxing in this case to drive behaviour would be better.

That the EU wants to reduce plastic waste is a good objective; however, the EU is only responsible for 3% of the plastic in the ocean, while 80% comes from Asia. If we are really serious, we should tax all imports from Asia, or at least those countries that cause a lot of plastic pollution, and use the money to deal with the plastic waste to create infrastructure in those countries. The European taxpayer pays in one way or the other, but from a global standpoint this would have a much bigger impact.

How do you think the European plastic levy will condition the development of compostable bioplastics?

This is unclear to me. What I do think is that the drive towards sustainability will continue for the next 50 years; after all, sustainability will become the entry ticket, the right to play in the industry of the future. While we need to do all we can to stop and reduce the plastic pollution, in the long run global warming will be the much bigger problem. So the pendulum will swing back from oceanic plastic pollution, i.e., from the end-of-life to the beginning-of-life, thereby reducing global warming. When we realize that 2% of global greenhouse gases (1.9% according to a 2015 study) come from unmanaged landfills, you suddenly see bioplastics in a different light, because these bioplastics divert biomass from the landfills which helps to reduce these global greenhouse gases.

Should EU Member States integrate the plastic levy with plastics tax in their own countries, or leave them separate?

I think an overall waste management concept supporting the plastic levy should be established – Italy probably has the clearest one although it’s not always implemented – but the levy should be combined and targeted to support this concept; just the tax by itself doesn’t make sense to me.

Composting in Europe has not had a uniform development in the individual countries: would a different regulatory framework be necessary, or should each country be given the freedom to define their own recovery objectives through composting?

I think there are two problems: the final objective of waste treatment should be defined and that’s up to the EU. For the transition, we have to accept that certain infrastructure already exists in certain countries. You have countries that predominantly incinerate now. It must be clear that the goal is to compost this biomass for which it first needs to be separated. There is still too much household biomass that is incinerated – 5 million tonnes in Germany, for example – which not only creates waste in itself, but also decreases the value of the residual household waste, which could be more easily separated and recycled.

The second biggest challenge is labelling. Each European country has a different way of indicating where the waste should be going in the end: to the green bin or the recycling bin along with the result. Because the goods are flowing freely, this confuses the customer. I think having two or at most three bins where things go would make the separation process much easier.

Consumers have difficulty distinguishing between biodegradability and compostability: do you think it would be better to use just one term?

There is some misunderstanding because the professionals don’t use the correct terms. I don’t think we can stop using biodegradability, as it’s an established term. But the professional should use the correct nomenclature and that means“industrially compostable according to EN13432.” As an analogy, if we say it’s 30 degrees outside, we say 30 degrees Celsius, not Fahrenheit. We need to indicate the testing norm at the end, otherwise you confuse people.

In Italy, industrial composting has developed unevenly from region to region: what would be the best way to help producers of bioplastics, converters, user companies and consumers?

The easy answer is to implement the law, but the fact that it’s not fully implemented implies there are obstacles. You can say apply the law, but if the money isn’t there to build the infrastructure, it’s really a challenge. However, Europe has the capability and the money: take the Covid recovery fund which amounts to 700 billion euro. An excellent way of using part of this money would be to build the infrastructure for recycling and composting. The resulting compost would really help to regenerate the soil.

To now, industries, governments and media have always incentivized composting as a solution to disposal. But there is another serious problem that is rarely addressed – the depletion of soil organic carbon. Who should be talking about LULUCF? (Land use, land-use change, and forestry).

Again, let’s look at the big picture. Yes, we have a lot of depleted soils, and it loses land. However, Europe has enough land to generate the biomass. The big problem in Europe is that in order to create a bio-based economy, we need to create raw materials at competitive prices, and up to now that’s a challenge. Farmers don’t want to produce to world prices. Europe will need to decide how to incentivize its farmers to produce in order to create the biomass, which is a requirement for a bio-based society.

By composting correctly, we help to bring the biomass and the carbon back to the field as valuable organic carbon. Globally, 26% of global greenhouse gases are emitted by agriculture; 20% are consumed and 6% of these are lost due to food waste, so we could save 6% of global greenhouse gases by eliminating this waste. Plastic production emits about 1.3% (5% of the 26%) of the greenhouse gases in the food production. So even if we drastically increase the plastic for food packaging to reduce the food waste, overall we still drastically reduce the global greenhouse gases.

In addition, think the EU should ask the retailer, brand user, or company to define the end-of-life option from the packaging’s conception. For example, if I decide to pack milk in a polyethylene bottle, what’s going to happen to this bottle after the milk is consumed? And then the logical next step is to follow through and ensure the infrastructure exists.

Plastics, or biopolymers, also have to learn from paper, glass and metal, for instance. I think that technology can help here: QR codes could provide much more information on what is to be done with a product that has fulfilled its purpose. End-of-life has to be seen as part of the life cycle – birth, life, death – and death has to be included into the design of a product.